Ownership of the South Pacific Islands – Present Day Colonialism

The South Pacific is a vast sea of islands a sprawling archipelago that covers over 800,000 square kilometres across the globe’s largest ocean. Despite its enormous area (roughly 15% of the Earth’s surface), the region’s population is tiny, only about 2.3 million people. These islands are grouped into Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia. Fiji, New Caledonia, Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea are included in Melanesia; Guam and Palau in Micronesia; Samoa, Tonga, Niue, Cook Islands, French Polynesia and others in Polynesia. Indigenous Pacific cultures are extraordinarily diverse – Papua New Guinea alone has hundreds of languages – yet most islanders share Austro-Asian roots and close spiritual ties to the land and sea.

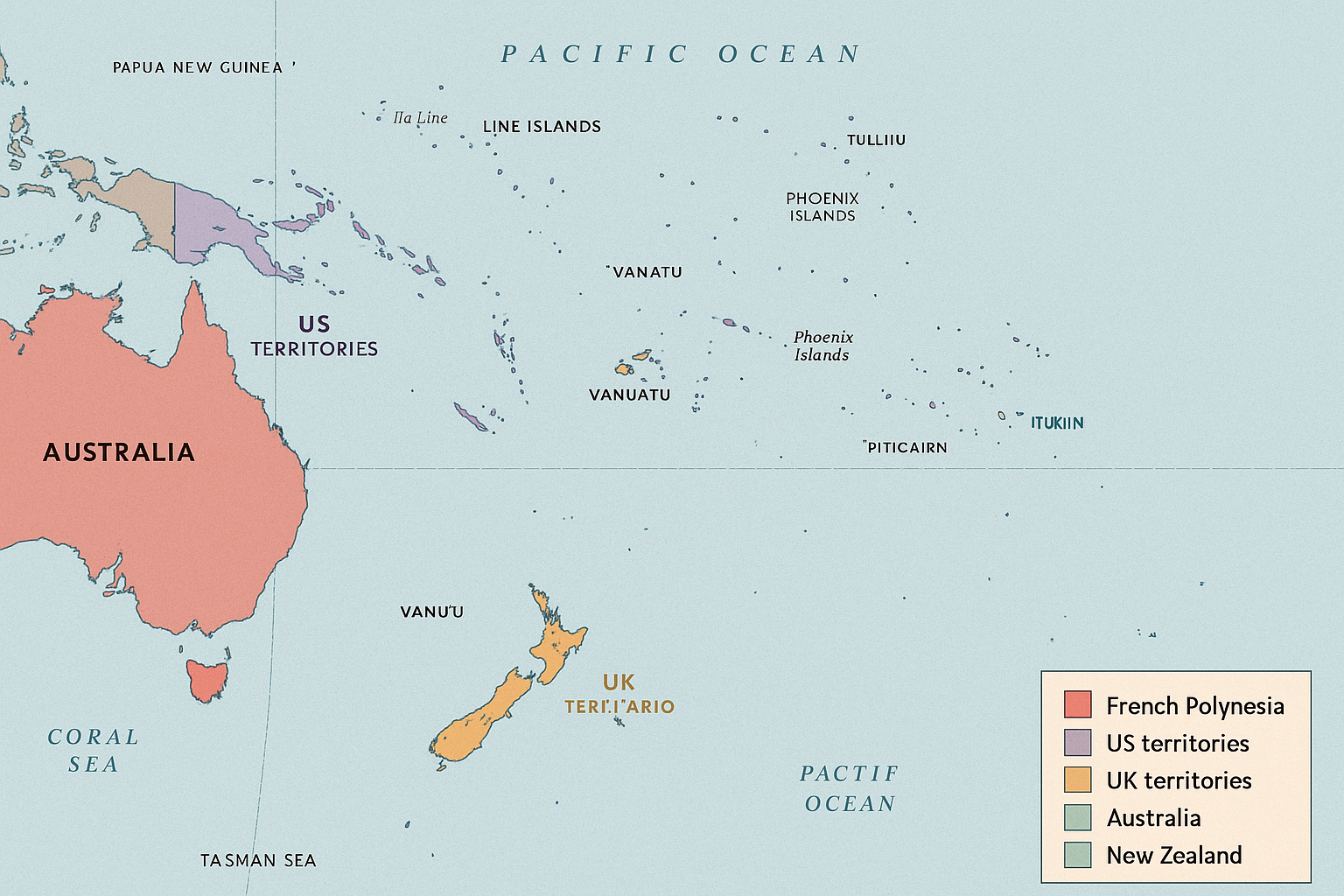

Today the Pacific Islands include a mix of independent nations (Fiji, Samoa, Tuvalu, etc.), freely associated states (the Cook Islands and Niue with New Zealand), and external territories / dependencies controlled by Australia, France, New Zealand, and the United States. Pacific populations are small (from just 12,000 people in microstates like Tuvalu or Nauru to some 900,000 in Fiji) and even these are scattered across a substantial ocean area. The consequent isolation coupled with the small size of the islands as well as under-development leaves these Pacific societies especially vulnerable. Infact the World Bank labels them as “among the most vulnerable countries to the impacts of climate change and natural disasters”. Rising seas, cyclones and loss of biodiversity loom over all islands, magnifying their existential threats, tenuous sovereignty and severely restricting their development choices. These factors have contributed to their being colonised in the past by richer and more opportunistic nations; something that still endures in parts till date.

The colonial story of the Pacific islands began centuries ago with European explorers and missionaries. Spain, Britain, France, the Netherlands and later Germany and the United States carved up the islands amongst themselves through treaties, wars and occupations. By the mid-20th century almost the entire Pacific was colonized. Today only a few colonial relationships remain: for example, New Caledonia and French Polynesia are still under France; Guam and American Samoa under the United States; Pitcairn Island under the United Kingdom; Norfolk Island under Australia; and the New Zealand–associated territories Tokelau, Niue and the Cook Islands. These territories have distinct legal statuses but share one thing in common: their peoples do not fully control their own fate. Despite generations of independence and decolonization movements, external powers maintain constitutional “ownership” of these islands, and the debate continues over whether this is modern colonialism or something even more pernicious like neo-colonialism.

French Territories: New Caledonia and French Polynesia

France’s Pacific empire includes New Caledonia (Kanaky) and French Polynesia, each inhabited by indigenous Melanesian and Polynesian peoples (Kanak and Mā’ohi). Napoleon III annexed New Caledonia in 1853, declaring it a “département” and importing French settlers and convicts. Polynesia fell partly under French sway in the 1840s, and by the 20th century the islands of Tahiti, Society, Tuamotu, Marquesas and some others had become French colonies. These islands were used as atomic test sites (with 193 nuclear blasts in Polynesia between 1966–96) and strategic naval bases, while Kanak lands and culture were subordinated.

In theory, France now grants these territories substantial autonomy, but in practice Paris retains firm control. New Caledonia is a “sui generis collectivity” governed under the 1998 Nouméa Accord. It has a local Congress and government, yet France still holds key powers (defense, currency, justice) and Paris sends military and police reinforcements to quell Kanak unrest. In 2018–21 New Caledonia held three independence referendums; all were won by the anti-independence side amid large scale rigging. That is why the pro-independence Kanak largely boycotted the 2021 vote. As the Kanak leader Billy Wetewea told Te Ao Māori News in late 2024, the French government dishonoured its promises under Nouméa by violently repressing protests and “applying these kinds of methods” against Kanak communities. Indigenous Kanak leaders call this a continuation of the colonial system: “Colonialism is not finished,” said one Kanak elder in September 2024, calling France’s New Caledonia occupation a “neocolonialism in the 21st century”. Echoing this, French activist and scholar Patricia O’Brien observes that the recent riots expose France’s “colonial legacy” and the Kanaks’ ongoing struggle for self-determination.

French Polynesia (Tahiti) has had its own surge of independence sentiment. Until recently Paris largely ignored Polynesian demands for sovereignty, even moving to bar them from the UN decolonization list. But by 2023-24 pro-independence parties won decisive elections (the Tavini Huiraatira party took 38 of 57 seats in 2023) and now lead the territorial government. Indigenous leaders like Moetai Brotherson (Tahiti’s president) publicly denounce decades of French nuclear testing and demand control over their nuclear history and resources. Brotherson addressed the UN General Assembly in 2023, calling for the “ownership” of Tahiti’s lands and seas after they were used for bombs, and demanding a transparent decolonization process. Even the French Senate in late 2024 acknowledged that French Polynesia needs a “new partnership” or “greater autonomy”. The fact that France must now publicly endorse its Pacific possessions as “overseas countries” and propose autonomy reforms under UN scrutiny underscores the colonial question: these islands, after centuries, still have not shaken off the imperial yoke.

United States Territories: Guam and American Samoa

In the vast Pacific, the United States today holds Guam and American Samoa as insular territories – essentially colonies without a path to full statehood. Guam was a Spanish possession until 1898, when the U.S. seized it in the Spanish-American War. It is now an “unincorporated organized territory” of the U.S., meaning Guamanians are U.S. citizens but have no voting representation in Congress. Guam has its own elected governor and legislature, but Congress has supreme authority. As Guampedia notes, Washington has repeatedly rebuffed Chamorro calls for greater self-rule or independence, citing Guam’s small size and strategic military value. For example, a 1979 U.S. report flatly declared that Guam would not be allowed independence or statehood due to its importance as a Pacific base. Guam remains on the UN’s list of Non-Self-Governing Territories to this day.

American Samoa’s story is even more pointedly colonial. In the late 1800s the U.S. Navy negotiated its way into Eastern Samoa (Pago Pago) while Germany took the western islands. From 1900 onward American Samoa was administered by the U.S. Navy (later the Department of the Interior), its people given only the status of “U.S. nationals”, not full citizens. Today an American Samoan born on the islands is a national but has no automatic U.S. citizenship. They have U.S. passports and can serve in the military, yet they cannot vote in U.S. elections or hold certain federal offices without naturalization. Local leaders have fought this vestige of colonial law – one civil rights lawsuit (addressed in Honolulu Civil Beat) argues that denying them citizenship violates basic democracy. The judge’s decision in 2021 upholding American Samoa’s unique status underscored the anomaly: as one Alaskan attorney for Samoan plaintiffs put it, U.S. territories like American Samoa operate under an “undemocratic colonial framework” imposed by decisions made in Washington a century ago. In practice, American Samoa’s “autonomy” is limited: the U.S. Navy once banned Samoan women from leaving their homes after a disaster unless accompanied by a man, and Washington still disallows any change to their nationality without Congressional approval.

In both Guam and American Samoa, indigenous people continue to resist this colonial order. Chamorro activists in Guam have petitioned the UN and organized plebiscites demanding a choice of independence, free association, or statehood. In 1977 Guam held its own plebiscite, showing strong support for independence, but Washington simply ignored it. In American Samoa, grassroots leaders and lawyers bring cases and appeals, insisting that the territories’ unequal status must end. American Samoa’s leaders argue that birthright citizenship was arbitrarily withheld for racist reasons in the 1930s, and today the same lines of dissent appear in every small town. The “Right to Democracy Project” formed in 2019 by activists from Guam and American Samoa explicitly calls out the colonial nature of the U.S. system, vowing to “dismantle the undemocratic colonial framework” still governing the Pacific island peoples.

Britain’s Last Outpost: Pitcairn Islands

The Pitcairn Islands are a tiny speck of Britain’s old Pacific empire. Settled by the mutineers of the HMS Bounty in 1790 and their Tahitian companions, Pitcairn today has only about 50 inhabitants across four islands. It is legally a UK Overseas Territory, administered from afar by a Governor in New Zealand. Locals elect a mayor and a small Island Council, but its powers are limited. Under current arrangements the Governor (a New Zealander appointed by London) can veto or amend any Pitcairn law. In recent years tensions arose when the Governor issued regulations without consulting the Council, prompting islanders to complain that their opinions were not sought in decisions that affect daily life. A new constitution in 2010 did introduce an Ombudsman and affirmed that the Governor must now consult the Council before enacting new laws, but final authority still belongs to the UK.

Pitcairn’s remote population has never held a referendum on independence – indeed, it relies on generous UK aid and supplies – but its situation illustrates a neo-colonial paradox: the islanders are “British” yet endure constant paternalism. One researcher notes that when a TV crew asked the locals “do you want independence?”, the islanders replied that if they had independence they’d have to pay taxes. Therefore, it is evident that on remote Pitcairn, colonial rule has become the default, inescapable system.

Australia’s Grip: Norfolk Island

Australia inherited a Pacific colony of its own when it settled Norfolk Island in 1788, later using it for convicts and eventually for Pitcairn’s descendants in 1856. For decades Norfolk enjoyed a curious semi-independence: from 1979 it had its own local Assembly and laws, with Canberra as a distant “associate” government. But in 2015 Australia unexpectedly abolished Norfolk’s self-government, asserting full control. This reignited resentment on the island, where many are proud descendants of the Bounty mutineers. As one columnist put it, Norfolk’s people “are resisting the forcible recolonisation of their homeland by Australia. Their self-government has been abolished, their parliament locked up, their freedom of speech curtailed”. Islanders formed groups like Norfolk Island People for Democracy to demand a new status. They argue their current colonial status is unjust: rather than integration with Australia, they want a free-association arrangement similar to what New Zealand has with Niue or the Cook Islands. Indeed, Norfolk activists explicitly cite Niue/Cook as models, complaining that Canberra “brought all Australian laws” to Norfolk and destroyed its special constitution. Australia’s actions on Norfolk echo a classic colonial tactic: centralizing authority, curtailing local rights, and marginalizing dissent. Those who speak up are often ignored or pressured by Canberra. Even a UN Special Committee report on decolonization has noted Norfolk Island as a case of an indigenous community fighting for self-determination against a former colonial power’s control.

New Zealand’s Realm: Tokelau, Niue and Cook Islands

New Zealand’s legacy in the Pacific includes three island entities: Tokelau, Niue and the Cook Islands. Each of these has a different relationship with NZ but none is fully independent. Niue and the Cook Islands are “self-governing in free association” – they have their own governments and constitutions (since the 1970s) and their people hold New Zealand citizenship, but NZ formally handles defence and foreign affairs on their behalf. Crucially, neither Niue nor the Cook Islands is a member of the UN or has a seat in international bodies as a sovereign state – their status is somewhere between autonomy and dependency. The UN has actually removed them from the list of non-self-governing territories after lobbying by NZ, recognizing their internal self-rule. Today both rely heavily on New Zealand: Niue’s budget is ~80% funded by NZ aid, and Cook Islands also receives large transfers.

Tokelau is still a “territory” of New Zealand. This tiny cluster of three coral atolls (population ~1,400) has long resisted full independence. In 2006 and 2007 Tokelau held UN-supervised referendums on becoming self-governing in free association with NZ. In each vote a majority of islanders did choose change (60.1% then 64.4%), but the result fell just below the 66.7% threshold. Credibility of the elections was also in doubt, with apprehensions that NZ had manipulated them to its advantage. Eventually, neither referendum passed, so Tokelau remains a NZ dependency (still on the UN non-self-governing list). Local leaders stressed that the margins were very close and that the failure was more a procedural technicality than a true rejection. Still, for now Tokelau has “no wish to be decolonized” according to some statements – though that sentiment may reflect satisfaction with the benefits of association or caution about viability.

Even in these cases with more autonomy, tensions surface. In 2025 the Cook Islands signed major deals with China on deep-sea mining and climate aid. New Zealand expressed concerns that the Cook Islands law “permits mining companies to take total control” of seabed resources. A Cook Islands prime minister responded that they are a sovereign government making their own decisions. This episode highlights how the interplay of local agency and external influence can be fraught. The free-association model gave Niue and Cook Islands a great deal of self-rule, but as soon as these Pacific microstates enter big-power arenas, questions arise about just how “free” their sovereignty really is.

Governance Today and Islander Resistance

Across all these territories, the governance structures vary widely, but a common theme is that ultimate power still lies with a distant metropolis. Australia, for example, now legislates laws for Norfolk Island that the Islanders themselves had never passed. In New Caledonia and Tahiti the French Parliament in Paris can override local decisions, and French judges have recently detained Kanak leaders on controversial charges related to protests. In Guam and American Samoa, the U.S. Congress and president hold sway; Guam has had multiple plebiscites (1976, 1982), all chose to remain a U.S. territory rather than independence, while American Samoa’s leaders periodically petition Washington for greater rights (so far, unsuccessfully). Pitcairn’s Council cannot levy taxes or change the constitution without the UK’s approval. Even Niue and the Cook Islands, though largely self-governing, cannot amend their basic status without NZ’s consent (and NZ still appoints their head of state’s representative).

How do islanders respond? Often with resistance movements and demands for self-determination. In New Caledonia, Kanak political groups (like the FLNKS) organize marches and strikes. During the 2024 unrest, pro-independence leaders formed barricades to block roads in Nouméa – desperate acts of protest against a constitutional reform they see as diluting Kanak voting power. One Kanak activist videoed himself calling on people to “maintain all forms of resistance” until France rescinds the contested electoral change. Across French Polynesia, groups like Tavini Huiraatira campaigned openly for “auto-détermination” (self-rule), and voters twice elected pro-independence majorities in their assembly.

In Guam, Chamorro leaders have set up a ‘Commission on Decolonization’ (mandated by the UN) and held local polls on status (independence or statehood). Even if these votes have favoured remaining linked to the U.S., they are a sign of Guam’s political awakening. Some Guamanians have travelled to New York to plead their case at the UN Special Committee on Decolonization, emphasizing that being on the world list of “16 Non-Self-Governing Territories” obligates the U.S. to allow a genuine choice of future. In American Samoa, civic groups regularly submit petitions to Congress and the courts, and Samoan churches and chiefs often weigh in on territorial issues. Samoans in Hawaii, Oregon and California (where many live) hold rallies and write to their representatives, arguing they should have the same civil rights as mainland citizens.

Pitcairn’s tiny community finds a voice in tourism and media; when the UK briefly allowed Pitcairn women to vote in the early 2000s, it was a local headline victory. On Norfolk Island, local activists stage regular protests and sign petitions. The grassroots group ‘Norfolk Island People for Democracy’ won the world’s attention by proposing that their island adopt a free-association status modelled on the Cook and Niue arrangements. They even briefed the UN Special Committee on Decolonization about their plight. Their message is clear: “We want the same rights and respect as other indigenous peoples like Māori or Niueans” – in other words, an end to being treated as Australia’s backwater dependency.

Even in “free association” cases, islanders push back. Tokelauans in 2007 cheered when their referendum came close enough to feel like a victory; years later they still complain if Wellington tries to postpone or influence local laws. Niueans occasionally debate whether to become a full UN member, though most are cautious, knowing their economy might not survive true independence. Cook Islanders have elected governments across the spectrum: some leaders openly court China and other big powers, seeing NZ’s influence as just another form of colonial dependence. (In 2023 the Cook Islands voted to rejoin the UN’s Non-Self-Governing Territories list and invited UN monitors to observe a self-determination referendum – a dramatic reversal.)

A powerful sign of resistance is how Pacific peoples see each other as united. Kanak leaders often invoke solidarity with Māori in New Zealand, with Aborigines in Australia, and even Chamorros in Guam. One Kanak youth told Te Ao Māori News that “all Pacific people – Vanuatuans, Māori, Kanaka, West Papuans, Chamorros – are brothers and sisters… our roots are the same”. Such pan-Pacific indigenous identity has grown in recent years. When France sent 7,000 troops to New Caledonia in 2024, protests erupted not only in Nouméa but across the Pacific via social media, in cities like Suva, Auckland and Honolulu. This shared mood is antithetical to any notion of tranquil neo-colonial contentment. Rather, it is insurgent: it frames present-day governance of these islands as an injustice that must be challenged.

Modern and Neo-Colonialism: 21st-Century Imperialism

Are these frozen colonial relationships simply anachronisms, or examples of something deeper? Many analysts argue that modern colonialism is alive – not as many flags flying in the Pacific, but as economic and strategic domination under friendly guises. Critics use terms like “neo-colonialism” to describe how external powers still reap the benefits and strategic rents from Pacific islands, often while claiming to “develop” them. For example, France’s continuing military presence (navy in Polynesia, troops in New Caledonia) is sold as guaranteeing stability, but indigenous Kanaks see it as an occupying force quashing their homeland. In the Chamorro context, an attorney for Guamanians calls the status quo an “undemocratic colonial framework”, echoing the sentiment that legal technicalities (territorial status, U.S. statutes) create a thinly veiled empire.

Neo-colonialism in the Pacific often centers on resources. Big powers remain eager to exploit Pacific fisheries, minerals and strategic locations. French interests in New Caledonia’s nickel, Tahiti’s seabed claims, or Australia’s interest in Pacific uranium (Norfolk’s government banned nuclear mining in 1990) all recall an extractive logic. Climate change has only intensified this: wealthy nations produce most emissions, yet low-lying Pacific atolls suffer first. Pacific islands have emerged as front-line “climate refugees” and activists. When the Western media chronicled island nations at UN climate talks, Pacific leaders lambasted the West for a colonial disregard of their future. Even environmental disputes echo the old patterns: activists have likened proposed deep-sea mining off Papua New Guinea or Fiji to a new colonial plunder. Greenpeace writer James Hita poignantly noted that a ship planning to mine the deep Pacific was named after Captain Cook – “a stark reminder of the ongoing legacy of colonialism and exploitation”. In his view, extracting seabed minerals without full indigenous consent and benefit is “a form of neo-colonialism” that perpetuates the abuses of Cook’s era.

Economically, many Pacific islands remain heavily dependent on aid from their administering power, a classic colonial dynamic. Niue cannot balance its budget without NZ subsidies, and its citizens all move freely to New Zealand for work. The “Blue Economy” of ocean tourism and fisheries is often serviced by foreign companies rather than local businesses. Critics point to foreign logging companies in Solomon Islands or atoll leasing arrangements as modern exploitation under the banner of development. The war over digital infrastructure and surveillance is also a new front: when Australia funded fibre-optic cables, observers asked if it was benevolence or a bid for data dominance. Even COVID-era vaccine deals and pandemic aid have had strings attached, leaving Pacific leaders wary of big-power influence masquerading as assistance.

These factors – military bases, resource grabs, corporate fishing, aid-dependency – compose a neocolonial mosaic. Islanders know the drill: the language of partnership and development from capitals often masks the reality of unequal power. They see that their lands are valued by others not for the people who live there, but for what those lands offer in global games of power. When Kanak activists declare “we can’t negotiate our identity” and demand “full sovereignty”, they are speaking against a system that still treats them as pawns. When Niue’s prime minister visits China or when Tokelau’s council complains about Auckland’s budget cuts, they emphasize that “colonialism has no place in today’s world” – a stance even the UN Secretary-General echoes annually.

In sum, the “ownership” of South Pacific islands today looks much like traditional colonialism with new packaging. Lands once declared imperial now have democratic façades – local assemblies, referenda, UN committees – but the underlying absence of true autonomy leads many to call it colonization by another name. As Kanak leader Daniel phrased it, “the anti-colonial insurrection is a war against the neocolonialism in the 21st century.” Whether one agrees with that militant framing or not, the sentiment captures how many Pacific people feel about the grinding legacy of empire still woven into their present.

India and the South Pacific: New Ties in the Indo-Pacific

In recent years, another country has been extending its reach across the Pacific – India. Geographically distant, India nevertheless has meaningful historical, cultural and strategic links with this region. Perhaps the most salient is the large Indo-Fijian diaspora in Fiji. Between 1879 and 1916, the British brought over 60,000 Indian indentured labourers to Fiji to work at sugar plantations. Today Indo-Fijians comprise about one-third of Fiji’s population. Although many emigrated to Australia, New Zealand, the US and Canada in the late 20th century, they still maintain cultural ties to India through religion, language, and family connections. This diaspora serves as a natural bridge. (India’s Prime Minister Modi even held a small meeting with Fiji’s minority leaders during a Pacific tour in 2023, emphasizing common roots in colonial history.)

More broadly, India’s strategic vision, often termed SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region) or the Indo-Pacific Ocean Initiative, has officially embraced the Pacific Islands. In 2014 India launched FIPIC (Forum for India–Pacific Islands Cooperation) to strengthen ties with 14 Pacific nations. Since then, India has hosted summits in Suva, Jaipur and Port Moresby, and has engaged bilaterally on trade, tech and climate. India’s approach leans on soft power: cultural events like Yoga Day celebrated in Samoa, scholarships for Pacific students in India, and Bollywood films aired on Pacific TV. Infrastructure and aid are also key. Notably, India has sent medical and development aid in line with Pacific needs: in late 2024 India dispatched haemo-dialysis machines and water purification units to several island nations as pledged at the 2023 FIPIC summit. A photograph from that delivery – boxes labelled “Gift from people & Government of India” – captured the goodwill. India also helped fund Covid-19 vaccines and digital connectivity projects in the Pacific. Such gestures are presented as “South-South cooperation,” but they also clearly aim to deepen India’s footprint in a region increasingly contested by China and Western powers.

On trade, the volumes are still modest. In 2021–22 total trade between India and FIPIC countries was around $572 million, a drop in the bucket compared to Australia–Pacific trade. But India sees growth potential: Pacific fisheries, agriculture and tourism markets are on its radar. New Delhi has explored investing in fisheries projects in Fiji and is even talking with Kiribati and Vanuatu about renewable energy tie-ups. And Pacific officials, like the Cook Islands prime minister, welcome India’s interest as a counterweight to being courted by one side only.

Culturally, besides the Indo-Fijian link, India has engaged through educational and people-to-people ties. Swami Vivekananda Cultural Centres in Fiji and Papua New Guinea run language and yoga classes. In PNG’s capital Port Moresby, one sees people celebrating Indian Republic Day and attending cricket matches – a hobby Indians introduced during the colonial period that has caught on locally. Some Pacific Islanders trace distant ancestry to India (for example, in West Papua there are families with Indian forebears from the colonial era), though these are few. More often, young Pacific activists visit India on scholarships, and Indian NGOs work on the islands, establishing friendships.

Strategically, the Indo-Pacific is now a buzzword of India’s foreign policy. Pacific leaders are no longer “dots on the map” – as an Indian analyst put it, they hold vast Exclusive Economic Zones and a powerful voice on climate change. India pitches itself as a “friendly partner” who respects Pacific sovereignty and brings no imperial baggage. It has co-sponsored Pacific initiatives at the UN (notably on climate and sustainable development) and pushed the idea of shared challenges. In 2024, Jaishankar, India’s foreign minister, toured Fiji and Papua New Guinea, signing partnerships on cybersecurity, health and maritime surveillance.

Of course, critics may say India is also playing power politics, seeking to limit Chinese influence by courting these island nations. And indeed, China’s growing presence (loans, ports, even military visits in some islands) has alarmed all other players in the region. Yet India’s Indo-Pacific push is often framed in the Pacific as positive and welcome. Pacific Island Forum meetings now regularly include India in discussions, and some island leaders speak appreciatively of India’s “inclusive” approach.

In summary, India’s ties to the South Pacific run from deep historical currents to newly forged strategic ones. Indo-Fijians provide an organic link to India’s culture and diaspora. New Delhi’s FIPIC and bilateral initiatives build trade, aid and diplomatic bridges. And India’s role in larger forums underscores how the Pacific Islands, once sidelined, are becoming an integral part of Indo-Pacific geopolitics. As one Indian commentary put it, the Pacific nations are rich in resources and climate leadership and deserve India’s “support for multilateral frameworks” that address their needs. In activist language, many islanders welcome India as another voice that recognizes their agency – saying, in effect, “We won’t be owned by only one big power.”

Decolonization and the Future: Climate, Self-Determination, and Geopolitics

Looking forward, the future of the Pacific is at a crossroads shaped by several sweeping trends:

● Decolonization and self-determination: The unfinished business of Pacific decolonization remains on the table. Many communities – from Kanak in New Caledonia to Tokelau’s traditional councils – continue to raise the banner of self-rule. France has agreed in principle to another New Caledonia referendum after 2024, and French Polynesia’s leadership is demanding a new status vote as well. New Zealand and Australia occasionally engage in dialogues about greater autonomy for their territories. The UN Special Committee on Decolonization continues to review Pacific cases, and island leaders bring complaints to the UN every year. Activist voices insist that true decolonization means not just ballots but real power: controlling natural resources, making laws, and preserving cultures without foreign veto. The recent resurgence of indigenous identity movements (Māori, Pacific Islanders, even Hawaiians) bolsters these efforts – there is a shared sense that colonial boundaries should not trap them.

● Climate change and existential threat: No discussion of Pacific sovereignty can ignore climate. Rising sea levels threaten to wash away low-lying atolls in Tuvalu, Tokelau and Kiribati. Cyclones batter islands with increasing frequency. Pacific leaders have become the strongest voices at global climate talks, warning that entire nations could vanish. However, the countries still needed to sign off on self-determination. As the World Bank notes, Pacific societies “are among the most vulnerable countries” on Earth. This vulnerability can cut both ways: it can catalyze unity and demands for action, but it also exposes islands to neo-colonial exploitation (investors coming in to build shelters, or rich countries practicing climate mitigation experiments on islands). Activists warn that climate crisis itself is a form of neo-colonial harm – one island representative likened carbon-emitting nations’ behaviour to colonial oppression, calling on the world to “recognise the harm” caused by history and climate together.

● Strategic realignments: The South Pacific has become a strategic arena. The U.S. is reasserting its military footprint (recently drawing down Marines from Okinawa only to bolster Guam and other bases). China has signed security pacts with Solomon Islands and increased aid across the region. Australia and New Zealand claim to be Pacific neighbours (one famously rebranding as “Pacific countries” rather than just “NZ territories” in 2024) and have rolled out their own aid programs. India and Japan have stepped up engagement. Amid this, Pacific island states are pushing back on being pawns. For instance, the ‘Pacific Islands Forum’ (the region’s leaders’ body) has insisted on a binding code of conduct for foreign bases and resources in their waters. Islands like Palau have told both China and the U.S. that their base proposals need local approval. There is talk of a Pacific solidarity bloc on issues like fisheries protection and equitable trade. Importantly, many island governments now demand to be treated as equal partners: Australia and NZ were gently rebuked when they tried to speak for Pacific Islands at international forums. In sum, Pacific nations are trying to navigate a balance: welcoming development partners (from India to the EU) while asserting their sovereignty.

● Socio-cultural renaissance: A Pacific cultural revival is underway. Indigenous languages, arts, and governance models are being reinvigorated. This feeds into politics: a Kanak pro-independence rally might feature traditional dance; a Māori teenager in New Zealand might organize a solidarity chant for Hawaiʻi. This cultural resurgence is itself a counter-weight to colonial ideologies. Many island constitutions now explicitly protect customary land tenure and languages – rights that colonial administrations once suppressed.

Future autonomy efforts will hinge on this identity: all new status talks will debate not just political power but whose heritage is recognized.

In a word, the future of the Pacific islands depends on completing the decolonization journey while steering through a climate and geopolitical storm. If the past was carved up in European chancelleries, and the present is defined by foreign capitals’ involvement, islander activists insist the future must be decided on the islands themselves. Decades from now, the maps of sovereignty in the Pacific could look very different: perhaps a sovereign Kanaky (New Caledonia) and Tahiti, a self-governing Tokelau, a revitalized Norfolk in free association with Australia – or they might still be overseas territories. What is clear is that the tides of change have been raised by the voices of indigenous and local peoples, who will not quietly accept anything less than full respect and self-determination. As one Kanak elder warned, “We don’t have any weapons… But we will defend our land and our identity with everything we have,”a refrain shared by communities across the Pacific.

The struggle is framed in the language of justice and sovereignty, and in that spirit the South Pacific now stands at a flashpoint of colonial legacy and a new world order. All relevant parties – France, the United States, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, and increasingly China – will need to listen. Otherwise, decades of tensions and upheaval suggest that these “possession islands” could ignite conflicts of conscience and demand a reckoning. The sun may never set on the old empires that once ruled these islands, but here at the edge of that sunset, Pacific Islanders are insisting on a new dawn of freedom.