Jana Gana Mana and the Burden of History

Jana Gana Mana and the Burden of History: A Re-examination of the Anthem Controversy

Few national symbols in India evoke as much emotion, reverence, and periodic controversy as

the national anthem, Jana Gana Mana. Written by Rabindranath Tagore in 1911 and formally

adopted in 1950, the anthem has often been read not only as poetry but as history, politics, and

ideology compressed into fifty two seconds of song. The recurring question was the anthem

originally a tribute to the British monarch? refuses to disappear. To engage with it seriously, one

must move beyond surface level assertions and return to the political climate of December 1911,

the contemporary press reports, and the structure of Indian nationalism at the time.

This essay revisits that moment with a sharper historical lens, drawing on British and Indian

newspaper coverage, and situates Jana Gana Mana within the complex loyalties and strategies

of the early twentieth century Indian National Congress.

The Political Moment of December 1911

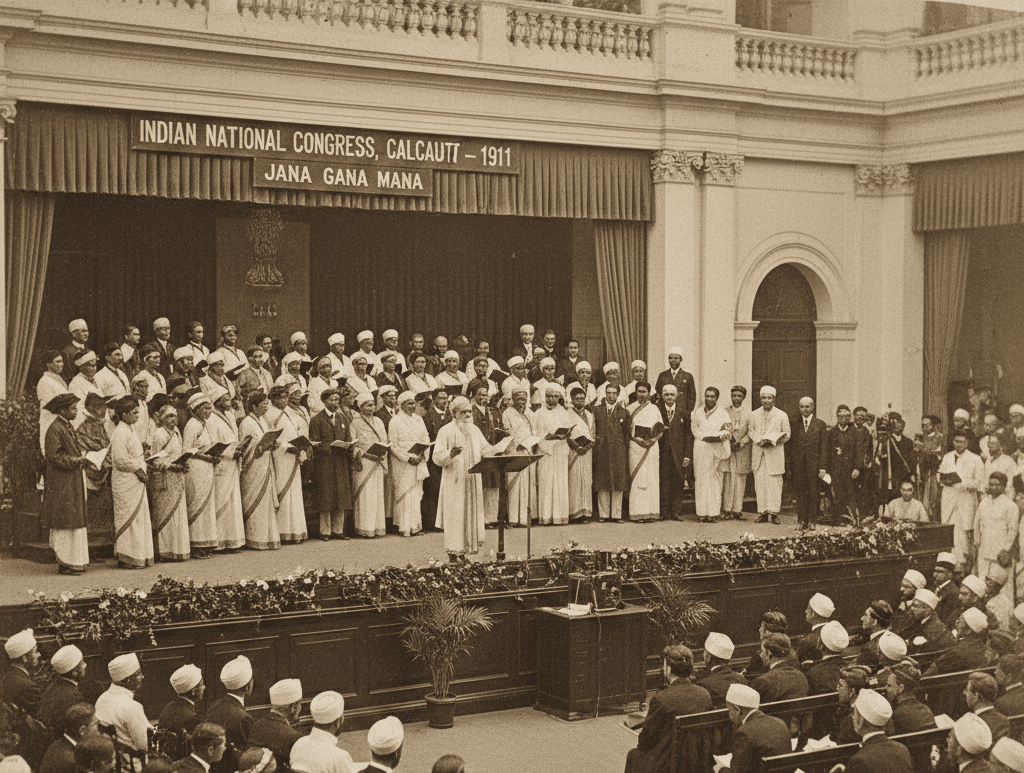

The song that would later become Jana Gana Mana was first sung on 27 December 1911,

during the Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress. This was not an ordinary Congress

session. Only weeks earlier, at the Delhi Durbar, King George V had announced two decisions

of enormous political consequence: the annulment of the Partition of Bengal and the transfer of

the imperial capital from Calcutta to Delhi. At that stage, the Congress leadership still operated largely within a constitutional, loyalist framework. The language of petitions, prayers, and loyalty resolutions was not unusual. Open demands for complete independence were still years away. It was in this context marked by cautious optimism and political pragmatism that the Calcutta session opened. The coincidence of the Congress session with the imperial announcements is central to understanding the later controversy. It created an atmosphere in which symbolic gestures were easily interpreted, or misinterpreted, as political endorsements.

What the British Press Reported

The confusion surrounding Jana Gana Mana can be traced directly to how British and Anglo Indian newspapers reported the events of that day. The Statesman (Calcutta) reported that the Congress session began with a song “composed by

Rabindranath Tagore specially to welcome the Emperor.” The Englishman echoed this view, describing the opening hymn as one written in honour of King George V. The Indian, another English language paper, similarly conveyed that a song welcoming the Emperor had been sung at the start of proceedings. These reports, read in isolation, give the clear impression that Tagore’s composition itself was a royal paean. However, they failed to distinguish between two different musical pieces performed during the session. Indian language newspapers and nationalist journals, particularly The Bengalee, offered a more precise account. According to these reports, the session opened with a devotional song composed by Tagore, addressed to a higher, abstract principle what Tagore later called the “dispenser of India’s destiny.” Only after this were formal resolutions of loyalty moved, followed by a separate song explicitly composed to welcome the King. The British press collapsed these distinct acts into a single narrative, largely because colonial journalism at the time often viewed Indian political gatherings through the prism of imperial loyalty rather than internal nuance.

The Structure of the Programme: Why Sequence Matters The order of events on 27 December 1911 is crucial.

1. A hymn by Tagore (Bharoto Bhagyo Bidhata)

2. A formal loyalty resolution to the Crown

3. A separate, explicitly royal welcome song

This sequence undermines the claim that Jana Gana Mana itself was intended as praise of the British monarch. The British press, unfamiliar with Bengali lyrics and inattentive to programme distinctions, reported the event as a single symbolic act. This misreporting was not malicious, but it was consequential. Once recorded in print, the idea that the song welcomed George V acquired a documentary life of its own, resurfacing decades later in polemical debates divorced from the original context.

Tagore’s Own Intervention

The most decisive evidence comes not from newspapers but from Tagore himself. In later correspondence, he directly addressed the allegation that his song was written in honour of the British king. His response was unequivocal: the “Adhinayak” of the song was not George V or any temporal ruler, but a metaphor for the guiding spirit of history and destiny. Tagore’s irritation at the persistence of the misunderstanding is evident in his later writings. He regarded the interpretation as intellectually lazy and culturally tone deaf, especially given the philosophical and spiritual vocabulary he employed.

Importantly, Tagore never sought royal favour through this song. In fact, his broader literary and political life consistently resisted subservience to imperial authority, even when he adopted a non revolutionary posture.

Why the Confusion Persisted

The endurance of the controversy tells us less about Tagore and more about how national symbols are retrospectively politicised.

Three factors explain its persistence:

1. Colonial archival dominance English language newspapers were preserved, cited, and

circulated more widely than vernacular Indian accounts.

2. Post independence nationalism After 1947, there was a heightened desire to purge

colonial residues, leading some to retroactively scrutinise symbols adopted during the

colonial era.

3. Simplistic readings of history The temptation to read complex political moments through

binary categories of “nationalist” versus “colonial collaborator” has repeatedly distorted

early twentieth century realities.

Beyond 1911: Other Layers of Controversy

Later debates over Jana Gana Mana such as the mention of “Sindh,” the absence of princely states, or the interpretation of words like Adhinayak are often wrongly conflated with the 1911 episode. These are separate issues arising from changing geography, post Partition trauma, and linguistic evolution. They do not retroactively validate the claim that the anthem was a

colonial tribute. Courts and constitutional authorities have consistently treated the anthem as a symbolic, poetic text rather than a literal political document, recognising its historical specificity without

demanding textual revisionism.

Conclusion: History, Not Hearsay

The controversy surrounding Jana Gana Mana survives because it sits at the intersection of colonial reportage, nationalist memory, and modern political anxiety. When examined carefully, the evidence does not support the claim that the anthem was composed to honour King George V. Contemporary British press reports misunderstood the event; Indian accounts clarified it; Tagore himself categorically rejected the imperial reading. What this episode ultimately reveals is the danger of allowing miss contextualised archival fragments to outweigh intent, sequence, and authorial testimony. Jana Gana Mana emerged

from a moment when Indian nationalism was still negotiating its voice under empire. To judge it fairly is not to demand ideological purity by modern standards, but to understand history on its own terms.

In doing so, the anthem stands not diminished, but clarified less as a relic of confusion, and

more as a document of India’s long, uneven journey toward self definition.