The Sanskrit-derived word Arishadvarga (अरिषड्वर्ग) breaks down into three components and refers to the “six enemies” of the mind that hinder spiritual progress in Hindu theology.

- Ari (अरि): Meaning “enemy,” “foe,” or “adversary.”

- Shad (षड्): Meaning “six.”

- Varga (वर्ग): Meaning “class,” “group,” or “collection.”

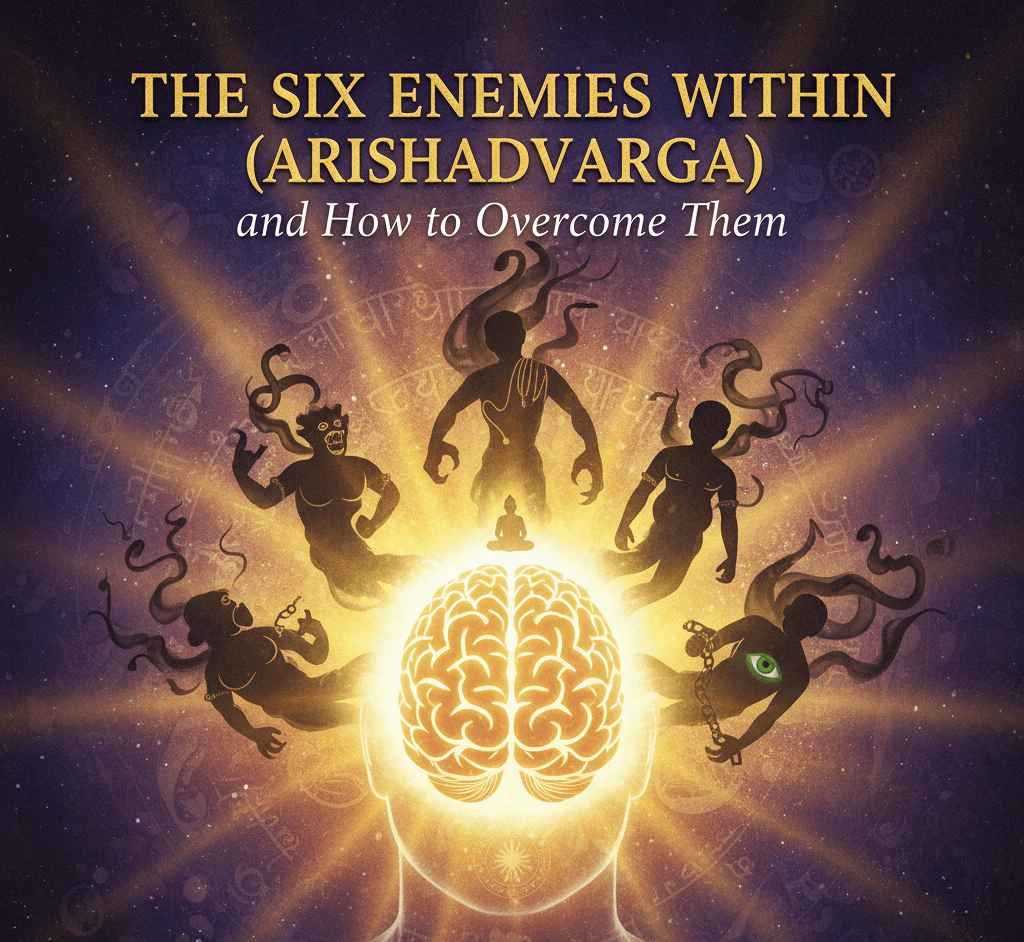

Together, Arishadvarga means “the group of six enemies.” These six internal vices are also known as Shadripu. These are: Kama (desire/lust), Krodha (anger), Lobha (greed), Mada (ego/pride), Moha (attachment/delusion), and Matsarya (jealousy). Together they bind the mind and soul, creating suffering and blocking spiritual growth. In practical terms, these foes are the intense cravings, aversions, and delusions that hijack our decisions and keep us restless or unhappy. For example, the Bhagavad Gita warns that simply dwelling on sense objects leads to attachment, which breeds desire, and when that desire is thwarted, anger arises. Likewise, unchecked lust or greed can consume a person’s entire life energy. Understanding these six inner enemies is the first step toward conquering them. In the sections below we explore each foe in turn – what it means, how it disrupts our lives, and practical strategies derived from ancient Indian spiritual wisdom, to overcome it.

How Do These Affect Us?

The six enemies are psychological/mental tendencies that pull us away from peace, wisdom, and contentment. Every human possesses these qualities, in different measure and the entire object of this enquiry is to assist us in enabling us to transcend these dissonances to as to be able to experience a state of existence relatively free of them. A straight-forward way to understand this is as follows:

- Kama (Desire/Lust): Intense craving for sensory pleasures, whether sexual, material, or ego-related.

- Krodha (Anger): Hostile rage or resentment that flares up when our desires or expectations are frustrated.

- Lobha (Greed): Insatiable appetite for more – for wealth, food, possessions or status – even when our basic needs are met.

- Mada (Ego/Pride): An inflated sense of self-importance or vanity; feeling superior to others.

- Moha (Attachment/Delusion): Clinging to people, things, or ideas as if they are permanent realities; being deluded about the true nature of things.

- Matsarya (Jealousy/Envy): Resentment or envy toward others’ success, possessions, or qualities, often coupled with a feeling of personal lack.

Each of these vices “hinders spiritual growth” by retarding our spiritual progress, or making us deviate from our path towards a pure and dissonance-free state of existence. These internal enemies may operate individually but usually collaborate with each other in myriad combinations, forming a kind of web. For example, desire (kama) often leads to anger (krodha) when unsatisfied, or to greed (lobha) when satisfied. Likewise, pride (mada) can fuel envy (matsarya), and attachment (moha) keeps us blind to life’s impermanence. The ancient psychologists noted that eliminating even one of these can weaken the others – for instance, Sri Buddha taught that conquering desire (kama) leads toward liberation. In sum, these six inner foes create an “environment of suffering” inside our own mind. Confronting them honestly is essential as a starting point for eventual self-mastery.

Let us now study each one of them in some detail.

Kama – Desire (Lust/Craving)

Kama (काम) is often translated as “desire” or “lust.” In Sanskrit texts it includes all intense cravings for sensual pleasure or comfort, not just sexual desire. It is the mind’s hunger for more – more food, more money, more status, more praise. The danger of Kama is that it never satisfies for long. Even when a particular desire is fulfilled, new cravings arise and the quest for ‘more’ never ends. The Bhagavad Gita portrays Kama as “the all-devouring, sinful enemy” that grows into anger. As Krishna says, lust alone is born of the passionate mode and later transforms into wrath. In practical terms, when we constantly chase desires, we become restless, anxious, and are perpetually dissatisfied.

How It Manifests

A person dominated by kama may spend considerable time pursuing pleasures – overeating, compulsive shopping, binge-watching, or endless ambition – always believing the next acquisition will bring happiness. This is likened to drinking saltwater: each sip only intensifies the thirst. The Bhagavad Gita advises that wise people do not delight in sense pleasures, because “such pleasures have a beginning but an uncertain end.” This reminds us that material gratification is temporary and ultimately unsatisfying.

How to Overcome Kama

The key is detachment and self-awareness. Instead of forcefully suppressing every desire (which often backfires), spiritual teachings recommend seeing each desire fully, objectively, clinically, in a detached way, disallowing it to cloud your perception or understanding of it. For example, one Gita-based guide suggests gently noticing the entire cycle of a desire – from its birth in the mind to its passing – and learning from that observation, rather than fixating on it. Practically, this can mean:

- Mindful Awareness: When a craving arises, pause and examine it. Notice its intensity, where it comes from, and how it changes moment to moment. This mindfulness (a kind of inner witnessing) weakens the grip of the desire.

- Balanced Lifestyle: Cultivate moderation in eating, sleeping, and consumption. Ayurveda and Yoga recommend a sattvic (pure, simple) diet and daily routine to keep the mind steady and less prone to cravings.

- Channel Energy Constructively: Redirect the vital energy behind desire into creative or compassionate activities (like art, learning, or volunteering). For example, the energy of romantic longing can be transmuted into devotion or service.

- Yoga and Meditation: Regular yoga practice and meditation (dhyana) calm the restless mind. Bhagavad Gita (6.35) acknowledges the difficulty of controlling the mind but says it is possible “by suitable practice and detachment.” Over time, the mind becomes less easily agitated by fleeting pleasures.

- Reflect on Impermanence: Remind yourself that all objects of desire are impermanent. As Gita (5.22) teaches, a wise person knows that earthly pleasures are esoteric, hence does not depend on them. This perspective—seeing through the temporary nature of craving—weakens their power.

- Devotional Focus: Many traditions suggest orienting desires toward higher goals. In Bhakti-yoga (path of devotion), one can use the energy of longing to deepen love for the divine, rather than purely worldly aims.

By steadily practicing these steps, one gradually sees that wants are like clouds drifting through a clear sky of awareness – noticeable, but not essential to one’s true happiness. Over time, the chain of desire loosens.

Krodha – Anger (Wrath)

Krodha (क्रोध) means anger or rage. It typically arises as a reaction to frustrated desires or injustice. When a goal or craving is blocked, anger erupts: “When the fulfillment of attachment is obstructed, it gives rise to anger,” says the Gita commentary. Indeed, Gita (2.62) warns that attachment leads to desire, and “from desire arises anger.” Anger is a powerful, fiery emotion. In small doses it can fuel courage or protect us from harm, but uncontrolled it poisons our judgment and peace of mind.

How It Manifests

Under stress, a normally mild person might snap, shouting, hitting, or seething internally. According to Yoga philosophy, anger is like “holding a burning coal with the intent of throwing it at someone else – you are the one who gets burned” (Buddhist analogy). Physically, anger tightens our muscles, raises heart rate, and can lead to shouting or even violence. Mentally, it clouds reason and memory. The Bhagavad Gita explicitly links anger to self-destruction: even righteous anger, if uncontrolled, can ultimately “destroy a person completely.” It is said that once Buddha remarked that “Anger is the punishment you give yourself for the failings of others.” Nowadays, modern science has clinically proven him right: anger disrupts normal bodily functions and the entire range of biological processes – from the physiological to mental to emotional, spiritual to attitudinal, and alters our immune system as well as stress levels, adversely.

How to Overcome Krodha

Key strategies involve cooling, releasing, and reflecting:

- Pause and Breathe: When anger flares, step back. Take a few deep, slow breaths. This simple break in the habit loop can prevent words or actions you’ll regret. Physically relaxing your body (e.g. unclenching fists) sends a message to the brain to calm down.

- Empathy and Perspective: Try to see the situation from the other’s viewpoint. Ask yourself: is this worth losing peace of mind? Often, grudges are based on misunderstandings. Practicing forgiveness (even silently) dissolves anger’s fuel.

- Use Humor or Release: Sometimes, a brief laugh or physical exercise (like a brisk walk) can dissipate tension. One practical tip from a yoga teacher is to laugh heartily for a few minutes each morning and evening. It may sound odd, but forced laughter can trigger real joy and reduce irritability, as proven by the success of ‘laughter therapy clubs’.

- Meditation and Mindfulness: Daily meditation builds a more stable mind so that rage has less power over you. Even a few minutes of observing your breath when you’re calm trains your mind to detach from agitation later. Techniques like mindful “journaling” about angry feelings can also help you see how trivial the cause may be in the long run.

- Study and Reflection: Remember that anger can often stem from mistaken views. The Upanishads teach that when the mind is attached to sense-objects it leads to bondage, but when detached it leads to freedom. Reflecting on these teachings during calm moments reinforces the habit of non-attachment.

- Self-Care: Ensure you’re not low on sleep, nutrition, or relaxation. Physical fatigue or hunger often lowers the “tolerance threshold” and makes anger more likely. Taking care of your basic needs makes it easier to stay patient.

By consistently applying these methods, the hot flame of anger can cool into steady composure. Over time, a person begins to break the chain where frustration turns into rage. In turn, clearing anger often reveals the deeper wound of fear or expectation underneath, which can then be healed.

Lobha – Greed (Avarice)

Lobha (लोभ) is greed or excessive lust for possessions. It is the never-ending “give me more” attitude. Unlike the healthy desire to have enough, greed wants everything – wealth, food, accolades, power – and it tells us it will die without them. In truth, greed can never be satisfied. The Gita starkly explains that even if one person were to acquire all the wealth, luxuries, and sensual objects of the world, his/her desire would still be insatiable. Greed blinds us into thinking that outer gain will bring inner fulfillment.

How It Manifests

We see lobha when people hoard resources, exaggerate expenses to show off or flaunt their riches, or feel resentful when others have something they don’t. It often arises from insecurity – thinking that if we don’t get more, we will somehow lack. In finance it looks like never feeling “rich enough,” always chasing the next big sale or investment. Emotionally it leads to envy and rivalry.

How to Overcome Lobha

Curbing greed involves cultivating contentment and generosity:

- Contentment (Santosh): Consciously practice gratitude for what you have. A daily habit of listing 3–5 things you’re grateful for can shift focus from “I want” to “I have.” Over time, you feel less compelled to always seek more. The Yoga Sutras list contentment as a vital discipline for this reason.

- Generosity (Dana): Actively giving (time, money, help) counterbalances greed. When we share, we weaken the fear of losing “our” things. Donations to charity or even sharing food/knowledge with others are ways to train ourselves that there is enough to go around. Paradoxically, giving often increases inner happiness and reduces cravings. St Francis Assisi was spot on when he said “It is in giving that we receive.”

- Simple Living: Adopt a minimalist mindset. Question your wants: do I need this new gadget, or am I just chasing a trend or trying to be a conformist, just another rat in the rat-race? Deliberately reduce consumption (e.g. buy only what you need). This not only saves money, it signals to your brain that you can be happy with less.

- Reflect on Consequences: Recall the Gita’s warning that desire, anger and greed are “gates of hell” leading to self-destruction. In practical terms, greed can destroy relationships (trust is broken by dishonesty or hoarding) and peace of mind (constant anxiety about loss). Keeping these consequences in mind can motivate restraint.

- Long-Term Thinking: Consider what is truly important in life: health, relationships, meaning. Often material gains bring only short-lived pleasure, while neglecting family or ethics for money leaves lasting regret. Reframing success in terms of well-being rather than wealth helps break the greed habit.

By intentionally practicing satisfaction with enough, one gradually loosens greed’s grip. The “hungry mind” slowly learns to find happiness in the present, rather than in the pursuit of more.

Mada – Ego/Pride (Arrogance)

Mada (मद) refers to excessive ego, pride, or arrogance – the belief that “I am better” or “I deserve special treatment.” It’s the inner voice that compares constantly: “I am smarter/richer/more important than others.” Justifiable Pride gives us a leg-up and a temporary glow of confidence, but beyond a point it also sets us apart and breeds isolation or jealousy.

How It Manifests

Ego can show up as boasting, looking down on others, or reacting strongly to criticism or failure. A proud person may feel entitled, cutting people off or demanding attention. In spiritual traditions, pride is seen as especially dangerous. For example, Sri Sathya Sai Baba observed that of all the evil qualities, mada (pride) is the worst, as it veils the inner divine consciousness. Pride essentially “blinds” us, making it hard to learn or empathize. The Sanskrit word for the cover over true understanding is avarana, and ego-pride forms this very cover over wisdom.

How to Overcome Mada

The remedy for pride is cultivating humility and self-awareness:

- Serve Others (Seva): Engage in selfless service without seeking credit. Serving those in need or working for a community cause shifts focus from “I” to “we.” It reminds us that everyone is valuable. Satsang (good company) and volunteering keep ego in check.

- Embrace Humility Practices: Simple acts like saying “thank you” often, admitting mistakes openly, or learning something new (as a beginner) can humble the mind. Deliberately putting yourself in the learner’s position (as the Bhagavad Gita suggests, the greatest teacher is the mind itself) opens you to others’ wisdom.

- Reflect on Interconnectedness: Remember that no one is truly self-made. We owe so much to teachers, nature, luck and society. Contemplating that “the divine is present in everyone” (as some scriptures teach) helps us respect others and see the ego’s smallness.

- Practice “Not I, Not Mine” (Neti Neti): In meditation, note each passing thought of ego (“I did this,” “I have that”) and gently dismiss it as “not I, not mine.” Over time this weakens attachment to ego-identities.

- Gratitude for Others: When feeling proud of an achievement, immediately think of the people who helped you or the effort of your team. This inoculates against solo glory.

- Teachings and Role Models: Study lives of humble figures (saints, social reformers, scientists) who downplayed ego. As Sathya Sai Baba said, our human values of truth and love lie beneath the “envelope” of these six enemies, and throwing off pride allows those values to flourish.

Humility is not thinking poorly of yourself, but seeing yourself accurately. As the ResearchGate psychology article notes, once pride is eradicated one “destroys all limiting self-absorbed states and reaches incredible equanimity.” In practice, the smaller the ego becomes, the more open and peaceful the mind is. In the end, the enlightened often perceive themselves as “No Me, only HE.”

Moha – Attachment/Delusion

Moha (मोह) is often translated as excessive, clinging attachment or delusion. It is the clinging of the mind to people, objects, or ideas as if they were unchanging and inherently “mine.” Moha keeps us entangled in illusions – for example, believing that possessions, relationships, or ego-identities are permanent and will bring lasting happiness. In reality, everything in life is temporary and constantly changing. Moha creates suffering by making us deny this truth.

How It Manifests

Commonly, moha shows as strong emotional dependence: being devastated at a breakup, over-protectiveness of children, or refusing to let go of past grudges. It also takes the form of ignorance: blindly following beliefs without questioning them. The key issue is lack of discrimination (viveka): confusing the transient for the eternal. As one upanishadic teaching says, “the mind alone is the cause of bondage or liberation – if attached to sense objects, it binds us, but if detached, it frees us.” Moha binds by never allowing the mind to rest.

How to Overcome Moha

The solution is cultivating detachment (Vairagya) and wisdom:

- Regular Meditation: Meditation trains the mind to observe without clinging. By quietly witnessing thoughts and emotions, you learn that they arise and pass away. This realization of impermanence (anitya) weakens attachment. Even simple mindfulness of breathing or body can remind you of life’s ever-changing flow.

- Reflect on Change and Death: Contemplating impermanence (e.g., meditating on the fact of death, or seeing old photographs of yourself) can help break the illusion. When you truly accept that nothing stays the same, you naturally loosen your hold on it. Enlightened minds often think of the ‘life’ they posses as a gift from God, loaned to them for some time and to be taken back whenever HE so desires. They are thankful for being given the chance to enjoy this divine gift and do not grieve when the lender takes it back (what we call ‘death’), since it was never theirs in the first place. They make no claim of ownership to it, being aware that a loaned item can never be owned by the recipient, its rightful ownership always stays with the giver.

- Practice Non-Attached Action: The Bhagavad Gita’s path of Nishkama Karma teaches doing your duty without attachment to the result. In daily life, this might mean doing your best at work but not obsessing over the outcome (“I will do my work with integrity, but I let go of worry about the result”). This shifts the focus to the present act, not the future fruit.

- Simplify and Let Go: Actively declutter your life – give away things you haven’t used for years, forgive old debts, end unhealthy commitments. Each “letting go” (even of a small material thing) is practice in detachment.

- Seek Higher Knowledge (Jnana): Study spiritual texts or philosophies that stress the difference between the real (unchanging Self) and the unreal (the body-mind, which changes). This intellectual wisdom supports experiential detachment. As a yogic saying goes: when the mind is not caught by sense objects, one “becomes free.”

- Devotional Surrender: For many, cultivating devotion to a higher power (Bhakti) helps reduce egoic attachment. By seeing ourselves as instruments of the divine rather than owners of outcomes, we relax the ego’s grip.

In short, taming moha means learning to love without clinging. When attachment dissolves, what remains is a calm contentment. Many mystics emphasize that true Prema (pure love) is utterly selfless, “totally free from desire.” As we practice, the heart naturally shifts from wanting to control life’s outcomes to embracing life as it unfolds.

Matsarya – Jealousy/Envy

Matsarya (मात्सर्य) means jealousy or envy – the resentful state when someone else has something we want. It is the “green-eyed monster” that turns another’s joy into our suffering. At its root, matsarya arises from insecurity and comparison: believing there isn’t enough good fortune to go around.

How It Manifests

Jealousy can lurk in subtle forms, like irritation at a friend’s success, or openly as malice. It often coexists with low self-esteem: we envy others because we feel “less than.” In a group, someone might consistently dismiss others’ achievements or engage in gossip to bring them down. Matsarya poisons relationships and joy: a jealous heart cannot genuinely celebrate another’s happiness.

How to Overcome Matsarya

The antidote is gratitude and self-acceptance:

- Practice Gratitude: Regularly remind yourself of your own blessings. Keeping a gratitude journal – noting what you have (family, skills, opportunities) – shifts focus from “They have, I lack” to “I also have.” Gratitude expands the sense of abundance in life.

- Rejoice in Others (Mudita): Consciously celebrate other people’s successes. When a friend gets a promotion, congratulate them wholeheartedly. Internally affirm, “May their happiness multiply.” This practice (called mudita in Buddhist terms) retrains the mind to take joy in others’ well-being.

- Address Insecurity: Use jealousy as a clue: ask “What do I truly want for myself?” If you find yourself envious of a trait or achievement, see it as inspiration. Instead of resenting the other person, set healthy goals for yourself. For example, if you envy someone’s fitness, start your own exercise routine.

- Avoid Comparison: In social media age, it’s easy to compare curated images of others’ lives to our own reality. Remind yourself that each life has unseen struggles. Focus on personal growth – run your own race.

- Increase Self-Worth: Work on building inner confidence and skills so that someone else’s shine doesn’t diminish you. Pursue learning or hobbies that make you feel accomplished. When you feel whole, there’s less room for envy.

- Service and Compassion: Helping others can break jealousy’s hold. Volunteer with groups different from your social circle. Serving people who have even fewer advantages can humble the mind and fill it with compassion rather than comparison.

By feeding gratitude and compassion instead of envy, the “white wolf” of positive qualities gains strength over the jealous “black wolf.” In time, matsarya loses its sharpness, and we cultivate a peaceful satisfaction with our own path.

Cultivating Freedom: Practices to Overcome All Six Enemies

Conquering the six enemies is a lifelong journey of self-discipline and inner work. Here are key practices drawn from yoga, scripture, and psychology that help weaken all these vices over time:

- Mindfulness & Self-Reflection: Make a habit of regularly observing your thoughts and emotions without judgment. Daily meditation (even 10 minutes of quiet sitting) increases awareness of when lust, anger, or pride arise. Journaling feelings can also reveal patterns (e.g. “I get envious when I scroll on social media late at night”). Self-awareness is the first power over these tendencies.

- Yoga and Pranayama: The eightfold path of yoga (especially the Yamas and Niyamas) provides moral guidelines (like non-violence, truthfulness, non-attachment) that directly counteract the six enemies. Physical asanas and breath-work (pranayama) calm the nervous system, reducing reactive emotions. For example, deep abdominal breathing stimulates the vagus nerve and calms anger. Regular yoga practice also instills discipline (tapas) and balance (mitahara – moderate eating) that diminish greed and anger.

- Study and Wisdom (Svādhyāya): Reading and reflecting on spiritual texts (Bhagavad Gita, Upanishads, or even modern psychology) gives insight into the mind’s tricks. Gita (6.5) reminds us that “the mind alone is one’s friend or enemy.” By learning its ways, we learn to redirect or deflate it. Even secular wisdom works: understanding cognitive biases (from psychology) can show how jealousy or anger clouds judgment. In any tradition, the more knowledge (especially self-knowledge) you gain, the less ignorance (avidya) fuels these enemies.

- Selfless Service (Seva) and Compassion: Helping others without expectation breaks the ego and greed. Acts of service (e.g. volunteering, mentoring, charity) shift focus from “what can I take?” to “what can I give?” Service also builds empathy, which softens anger and envy (when we see others’ struggles). In many spiritual paths, cultivating unconditional love (prema) is the ultimate cure: as one teacher said, filling the mind with divine, selfless love naturally “expels the six enemies residing in it.” Love dissolves pride, anger, and jealousy alike.

- Discipline (Tapa) and Moderation: Strengthening the will helps resist impulsive reactions. This can mean small fasts (e.g. a daily discipline of a cold shower or skipping an extra snack) or vows (like controlling the tongue or senses for a period). The Bhagavad Gita notes that a person “whose senses are restrained from their objects is of steady intelligence.” Building small disciplines teaches the mind that you are stronger than your impulses. Always apply moderation in all aspects – overindulgence in anything fuels the enemies of excess.

- Devotion and Surrender: Cultivating faith in a higher purpose can subdue pride and fear. Prayer, chanting, or devotional reading reminds us that we are part of a larger whole, reducing egotism and attachment. Gita (18.66) encourages surrender: “Abandon all varieties of dharma and simply surrender unto Me.” While faith is personal, its effect is often to give perspective – what seemed urgent (like ego or greed) now seems small when viewed in light of the infinite. According to Krishna, those who surrender can “cross beyond” the powerful six-fold material energies.

- Positive Community (Satsang): Surround yourself with honest, caring people who uphold truth and virtue. In good company, one learns from others’ examples of restraint and kindness. Avoid environments that constantly stoke desire, anger or gossip. As the Sai organization study notes, having “faith, courage, and love” around you assures protection from the six enemies.

- Laughter and Joy: Never underestimate simple joy. Regular laughter and light-heartedness actually diffuse anger and envy. Playfulness with friends or hobbies that make you blissfully engaged help you see life more lightly. A balanced life that includes fun will naturally curb the heavy grip of these vices.

Together, these practices form a comprehensive toolkit. No single technique eradicates all six enemies overnight, but steady application weakens them. For example, yoga and meditation calm the mind (reducing lust and anger), while service and humility practices target ego and envy. Over time, new, positive habits and attitudes grow (such as patience, generosity, contentment, and equanimity), and the old vices “die” like weeds in a well-tended garden.

Conclusion

The journey to overcome the six inner enemies is challenging but rewarding. These vices – Kama, Krodha, Lobha, Mada, Moha, and Matsarya – are powerful because they tap into fundamental human fears and desires. Yet every tradition agrees they are not invincible. By shining the light of awareness and virtue on them, we can transform weakness into strength. As Bhagavad Gita (3.37) proclaims: Lust (kama) is the sinful, all-devouring enemy, but knowing it as such is the first step to freedom.

In practice, this means being honest with ourselves about when we are controlled by craving, rage, greed, pride, attachment or jealousy. Then, with compassion and discipline, we gently steer the mind toward healthier patterns. Just as climbers ascend step by step out of a dark valley into sunlight, we too can climb out of negativity by cultivating mindfulness, selfless action, and love.

Every person faces these inner adversaries, but every person also has the potential to conquer them. With persistent effort – through self-inquiry, disciplined practice, and choosing love over fear – the once-daunting six enemies become teachers. They highlight where we need growth. In time, by “putting the bad in us out” and nurturing virtues instead, we create a calm, wise mind in which those enemies lose their power. The result is profound: a life lived with clarity, compassion, and inner peace.